The Roots of Traditional Dance

The community, or choral, dances of today have come to us from ancient times. These are dances requiring larger groups of dancers to complete the patterns. Dancers may be paired into couples but each dancer will dance with others in the group as often as with their partner. Square dances call for eight dancers, contras and reels are best done with twelve or more, and for the various circle dances, the more the better.

The contra dance is a choral dance. Circle and file dances, the basic forms of choral dances, can be traced back to the culture of the Stone Age. The English contra dance, a choral double file dance, has one characteristic, however, that seems to be uniquely English, according to Curt Sachs, in World History of the Dance, which is that the couples enter the dance gradually. "One after another the couples must move to the same melody, repeated over and over again, in the same figure pattern and keep moving in it until all the couples have entered."

Historically, there are some mentions of the contra dance at the end of the sixteenth century, and in 1650, John Playford published The English Dancing Master or directions for Country Dances, a collection of English country dances, containing about thirty-five of the long-ways contra dances. By the time the eighteenth edition of The Dancing Master was published in 1728 there were as many as 900 contra dances included. Contra dances were brought to New England by colonists in the 1600's and have been danced there ever since.

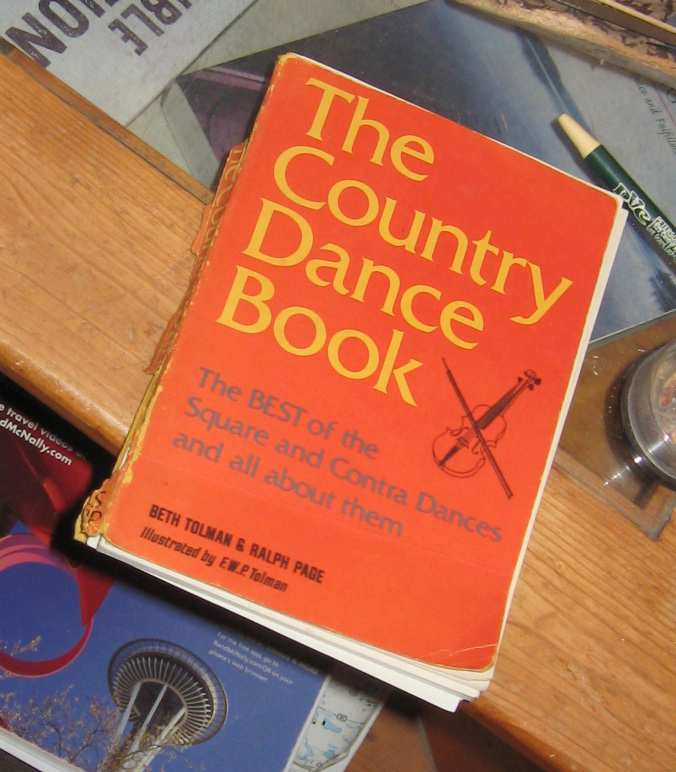

Ralph Page is a dance caller, teacher and dance session organizer from New Hampshire. In his book, The Country Dance Book: the Best of Square and Contra Dances and all about them, by Beth Tolman and Ralph Page, Ralph defines the word contra:

What, then, is a contra dance? Contra dances are dances danced in two contrary lines. The couples face each other, with the men in the left line, and women in the right. The first, third, fifth (and so on down the line) couples are active, or ones. The others are inactive, or twos. The actives dance down the set, dancing a set figure with each inactive couple. Meanwhile the in-actives are working their way up the set, dancing with each active couple they meet. When an active couple reaches the bottom of the set, they wait out one time through the dance, and then dance back up the set as inactive. Likewise, as inactive couples reach the top, they wait out once, become actives, and dance down, and so on. In many versions, active men and women cross to the opposite, or improper, side of the set. These are called improper contras. There are also triple minor contras, not so common anymore, where the second and third couples are both inactive, and alternate between second and third position as they work their ways up the set.

Going back to Curt Sachs, we find that the cotillion was a French dance of the 1700's, danced in a square of four couples. Among the many figures are les ronds, the grande chaine, and the moulinets. The grande chaine is a grand right and left, the moulinets, a star for four, and les ronds, a circle right and left. The cotillion evolved into the quadrille, a dance with five distinct parts, each with its own separate music. Ralph Page writes:

The Kentucky running set is an old dance from England that survived in the hills of Appalachia. Cecil Sharpe, a noted English folk-dance authority, found this dance in Kentucky in 1917 and wrote a booklet about it. He believed that it was one of the oldest dances in England, preceding the Playford dances of 1650. Apparently, it lost favor in the south of England, but continued to be danced in rural areas in the north of England and in Scotland until sometime in the 1700's, when it was brought to the Appalachian Mountains in America.

The dance is done with couples in a circle, with as many as will. The first couple visits the second couple and does a figure with them. They then move on to dance with the next couple. As soon as possible, the second couple moves out to dance with the third couple, and so on, until all dancers are involved in a looping continuous chain. The figures are very similar to the figures danced in old English singing games. Many of the figures seem to come directly from English country dancing, but in the running set there are no courtesy movements, such as the honours, siding, setting, arming, or turn single moves, so common in the English country dances.

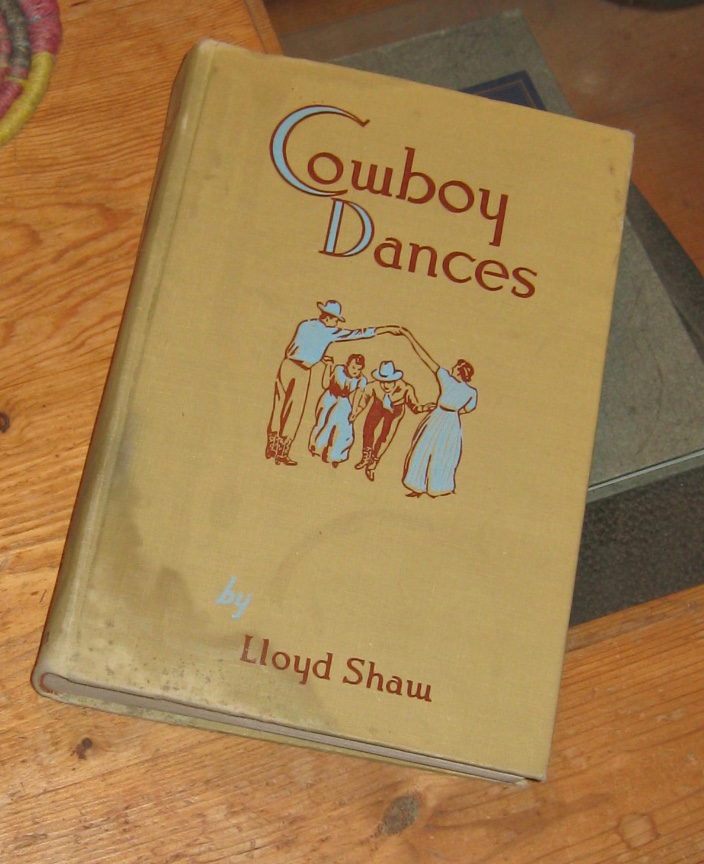

Lloyd Shaw, who spent most of his life working to keep square dancing alive and unspoiled, explains his theory of the origins of our American square dances in his book, Cowboy Dances. These Kentucky dances, he says, are "surely the chief forbears [sic] of the Western dance." The names of many common square dance figures, such as Lady round the lady, Birdie in the cage, Ladies in the center, Figure Eight, the visiting pattern, and the numbering of the couples around the ring, all seem to come from the running set. From the quadrille we get certain other figures, such as ladies chain, right and left through, as well as the bowing, saluting and other courtesy movements common in square dancing. "Distances were great in the West," says Shaw.

They needed something simple in pattern, with a running call to tell them what to do. And so, says Shaw, the simpler figures of the running set were fitted onto the framework of the more complicated New England quadrille to become the square dance.

The Music

The fiddle, broadly defined as a string instrument with a sound box played with a bow, dates back to at least the 900's A.D. in Europe, and its music has always been closely connected to dancing. European explorers and emigrants from different countries, primarily the British Isles, France, and Scandanavia, brought their traditions of fiddle music and dance to North America, and the music evolved, with more or less influence from Native American and African American music and dance, into numerous distinctive American styles: New England, Cape Breton, southern Appalachian, Western, Quebecois, Métis, Scandinavian, and Cajun to mention a few. The banjo, an American instrument in its present form, was brought from Africa and had a definite influence on the fiddle music in the Appalachian area.

In the days before recorded music, musicians were essential figures at the dance; when they played, people were moved to dance. The dancers' enthusiasm raised the energy level of the band, fueling the energy level of the musicians, which then led to greater excitement in the dance and so on.

Fiddle tunes are renewed each time they are played. Each new musician interprets them in a slightly or perhaps even vastly different way. The fiddle is typically the lead instrument in a dance band, sometimes even the only instrument. The fiddler plays both melody and rhythm with the bow strokes, and each fiddler develops a unique bowing style. The musicians enrich the living quality of the dance and the fiddler is the most important musician of all. The fiddler's job is to make people feel like dancing. The music is, after all, referred to as "Fiddle music." Jean Trudel, Canadian Ethnologist, writes:

"Fiddle," a woodcut by Jeanne Griffin O'Neil

Not only are fiddlers an important part of the dance community, but they, together with the dancers, create it. Without the musicians, who would move us to dance?

Our Regional Heritage

The Fur Trade Era

The Red River Valley's heritage of fiddle music and dance dates back to the earliest days of European colonization of North America. French traders and missionaries explored the region in the early 1600's, and English and Scottish traders were not far behind. The Red River of the North is part of the drainage basin of the Hudson Bay, and in 1670, King Charles II of England chartered the entire basin of the Hudson Bay to the Hudson Bay Company, proclaiming that "the said land be from henceforth called Rupert's Land." (Visit the Rupertsland Institute for more history.) For the next two hundred years, the Europeans and Native Americans of Rupert's Land engaged in the fur trade. Many of the French and Scottish traders took Native American wives, and their children and descendents became known as the Métis people. As documented by the Rupertsland Institute,

The Red River Jig is a prime example of the unique Métis fiddle and dance tradition. This dance is a competitive dance that incorporates the basic step of French Canadian step dance, and the fiddle tune features a truly unique blend of Native American and European rhythms. The book Mrs. Mike: the Story of Katherine Mary Flannigan, by Benedict and Nancy Freedman, provides a glimpse of the role of this dance in the camps and villages of the latter years of the fur trade in northern Alberta.

The pulsating beat of drums led us away from the games and up to the circle of dancers... The first dance called for the maidens and the young men of the tribes... The line of girls danced forward to the line of boys. On toe and heel they moved, ... and the young men surged forward, step, hop, step, in exaggerated rhythm.

A harmonica, playing "The Red River Jig," cut in upon the austere pattern of the drumbeats. [The Métis] ... had started a dance of their own. A little way back they cut pigeon wings and did the double shuffle, leaping and springing in the air. They drew a crowd ... that clapped hands and thighs in time to the harmonica. A fiddler joined them.

Some say that the Red River Jig is the unofficial national anthem of the Métis. Several dance groups in Manitoba include the dance in their performance repertoires, including the Asham Stompers, L'Ensemble Folklorique de la Rivière-Rouge, and Ça Claque!.

Sharing tunes at the old crossing, Huot Park, Red Lake River, 1995.

The Homestead Era

The Métis were pushed north and west from the southern Red River Valley by a number of political and ecomomic factors. The southern valley became territory of the United States in a land swap with Canada in 1818, fifteen years after the U.S. acquired the Missouri basin from France in the Loiusiana Purchase. This swap made the 49th parallel the boundary between the U.S. and Canada, effectively cutting off the southern extent of Rupert's land. The Ojibwe officially ceded the Red River Valley below the 49th parallel to the United States in the Old Crossing Treaty of 1863, and the territory was soon opened for homesteading and agriculture. Steamboats and railroads also made their way to the region in the latter 1800's, eliminating the need for the Métis ox cart trails between Winnipeg and St. Paul. So by the end of the 1800's, the Métis culture waned and a new wave of immigrants arrived from the eastern states and from Europe, including many Scandanavians, Scottish, Germans, and Irish, to establish the region's agricultural economy. These pioneeers, of course, brought their music and dance traditions with them, and the rural barn dance and house party culture took root.

"House Party," pen and ink drawing by Jeanne Griffin O'Neil

While working to complete her long interrupted baccalaureate degree at the University of North Dakota, Jeanne O'Neil conducted an oral history project on traditional cummunity dancing in the Red River Valley in th 1930's through the 1970's, Virgil McCann, age 84 of Thompson, ND, (interviewed by Jeanne in November, 2001) remembered square dancing in the Thompson and Hillsboro area before the Western-style clubs started, back when it was done in kitchens and living rooms:

My dad used to call. Back in the 30's, families would have house parties every Friday or Saturday night, we'd go to a different house each week. This was in the Thompson area, and Hillsboro, around there. In the winter, if it was stormy and the roads were bad, we'd hitch up the horses, and then just park 'em in the barn. We'd stay 'til after midnight, and make it home again, too. For music? Oh, there might be someone who played the fiddle, or piano, or a guitar player, or whatever, you know; they might not even be very good. It'd start out as a card party, and the winners would keep moving up to the next table until they were done, and then they'd want to dance. Some houses were fine for space, a big living room with oak floor, or they'd push back the furniture in the kitchen, wherever there was room. We'd usually have one or two squares. I suppose there were 20 to 25 people. Sometimes it was bigger, sometimes smaller, and some would just want to watch, or they'd take turns. I was kind of interested in watching my dad call. The first calling I ever did was at the High School. They wanted to have a square dance, and they knew my dad called, and they just had me do it. I did that a few times. The family dances just kind of petered out, they just didn't have them any more after awhile.

Caller Virgil McCann, 2001

I didn't square dance again until I was 45, when some neighbors started going to the square dance club in Grand Forks. I went for about two years. Harry Tack was the caller, and he showed us how to dance. Anyone who wanted to try could call, so I tried it, and I did okay. We used records then. I started the Thompson group too, the Thompson Tabbies, Toms and Tabbies, you know. They went for about 10 or 15 years, and then they weren't getting any new dancers, so they dissolved. And then Harry Tack , the caller for Shirts and Skirts, he quit, so I took over calling for that club. I started calling all around the state. Bismarck, Minot, and a lot of little towns in between. I got paid $25.00, and extra for mileage, if I went to Bismarck, I'd get $100.00. Often dancers would invite us to stay so we didn't need to get a hotel. My wife, Ruth, always went with me, and she'd dance whenever she was asked. I was calling every night of the week, sometimes. But in the last few years, I decided to give it up. I didn't like to travel at night anymore, and I broke my hip. The whole country has slowed down now. It started dwindling in the 1980's and 90's. I haven't been to the national meetings in the last five years, but every organization you talk to, people say it's nothing like it used to be. It's hard to get new people to come to the lessons. Even the regular dancers couldn't get anybody to come. One time, we advertised the lessons, and I went and set up, and nobody came. So I went home, too.

I did one dance for the Thompson Senior High this spring. They really liked it, they wanted to do it again. The kids learn so fast, if I was younger, I'd do it all over again.

Harry Tack of East Grand Forks, MN, had a different view about why Western square dance clubs died out. Interviewed by Jeanne O'Neil in 2001, he too remembered dancing before the clubs were started.

I got started dancing when I got out of the service, it would have been 1945 or '47. We used to have a lot of sessions in the basement over here in East Grand Forks. We used to go all over the country, having these dance parties in peoples' basements. One time, I invited some people over, they thought they were coming to a card party. I put on a record and got them dancing. They had a ball! Finally though, you could just see it peter out, it just folded up. That's when they started the club dancing. In the 50's and 60's. We met at the school, I had pull in the schools, I had a key to the building. Canadians used to drive clear down here to go to our dance, quite often. They were exceptional dancers. We used to have pie dances, too, people would bring pies, for after the dances. The conventions were the thing I liked, they were really beautiful. All the women would be there in their pretty dresses, you'd go upstairs and look down, and oh my word! It was really something to see. That would have been maybe late 60's and 70's.

And then it got to be club against club, each club had to be better than the other, and they'd start saying things like "Oh geez, he keeps calling the same old stuff ," and there would be competition between the callers. In old time dancing, they could do the same dance all night. I think that's what killed it, it just got too damn complicated. It got so the caller would take ten figures, put 'em one right after the other, and people would have to memorize all that. The average person wouldn't know all those calls, and they'd get disgusted and wouldn't come back. People used to be there to have a good time. Lots of times people could be square dancing and talking, all at the same time, just having a good time, a real good time. If they didn't get so complicated, and just have a good dance... At the old dances, the fiddler would be up there, and he'd do the calling. I say, if people like it, use it, just let 'em go, let 'em dance.